The Sum of all Knowledge

Posted on January 17, 2014

In the not too distant past, say the early 1600s, an educated person could know just about all there was to know, or all that was known. There weren’t many educated men, and almost no educated women, in those times. Lecture classes in college were given in Latin. An educated English person spoke at the very least both Latin and Greek, and probably some French, Italian, German, and maybe one or two other languages. Such a man would have a fairly in-depth knowledge of biology, medicine, literature (the classics, from the Greeks, Socrates and Aristotle, to the Romans, Cicero, Ovid, and Virgil), astronomy, zoology, mathematics, and a few other core areas of study. The term “Renaissance man” applied to such men. Of course we are talking about an extremely Euro-centric view of the world, a world composed mostly of white men in the England, France, or Italy of the time.

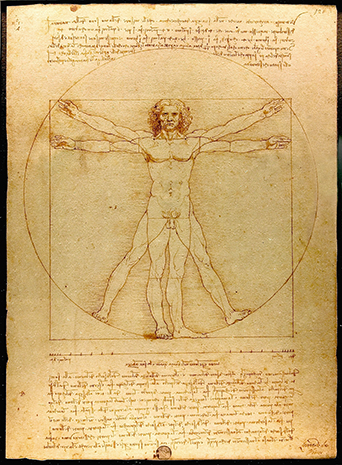

Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci, the quintessential Renaissance Man From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vitruvian_Man last modified on 19 November 2013 at 04:53

Today, thankfully, knowledge has exploded into the reach of almost everyone, of both genders, of every race and nationality. Today there are no generalists. No one knows more than the tiniest sliver of human knowledge. There are only specialists. This is of course infinitely better. There is no tyranny of the educated any more. The idea of a society ruled by a few rich and self-entitled white men, while the great masses of people were kept in poverty born of ignorance, is repulsive to us now.

Still, we can perversely envy the idea of living in a time when, if you were one of the very select, privileged few, you could converse with your peers, as limited as your knowledge was compared to what was unknown, and imagine yourselves as the repositors of the sum of all knowledge. You were almost god-like in your expansive understanding, as erroneous and incomplete as it turned out to be later in history.

Today villagers in remote Indian villages use cell phones. Everyone has access to the Internet except those who live in a few repressive authoritarian regimes. We are only at the beginning of a revolution in technology that will continue to spread the accumulated knowledge of humanity to more and more people. My own grandfather went from living in an impoverished Greek village on the coast of Turkey (“a day’s walk from Ephesus” he used to say), with a single well for water in the village square, and donkeys pulling wooden carts as the main mode of transportation, to seeing men walk on the moon, in a single lifetime.

Can there be any question that this is the most exciting time ever to have lived? But, what are we going to do with all this knowledge? Is it just going to devolve into “57 channels and nothing on”? Are we going to fritter away our lives using the technology for nothing more than video games and individual music players pouring sound into our “earbuds”? I hope not. Let’s hope the vast and exponentially growing sum of human knowledge will be used to improve the lives of all who live here, on this “mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam” (Carl Sagan).